I’m in an email group that is all in agreement that the U.S. healthcare system is exorbitantly expensive and needs reform. We come from wildly different backgrounds. The variety of perspectives is wonderful. However, a claim of some of the contributors is that aggressive medical therapy of cardiovascular disease (CVD) chronic disease care increases life expectancy by 8 years. This statement was based on a small Danish study called the Steno-2 trial, so let’s take a closer look at the Steno-2 trial.

Efficacy of Steno-2 Approach

This study randomized 160 patients into intensive vs. usual treatment groups, 80 in each arm. Usual care (for the majority of the trial) meant BP less than 160/95, hemoglobin A1c < 7.5%, total cholesterol < 250, no ACE inhibitor if the blood pressure was normal, and a few other minor targets; intensive care meant BP less than 140/85, hemoglobin A1c < 6.5%, total cholesterol < 190, and an ACE inhibitor even if the blood pressure was normal. Some of these numbers were lowered in the last 2 years of the 7.8-year primary study. This study generated several results papers.

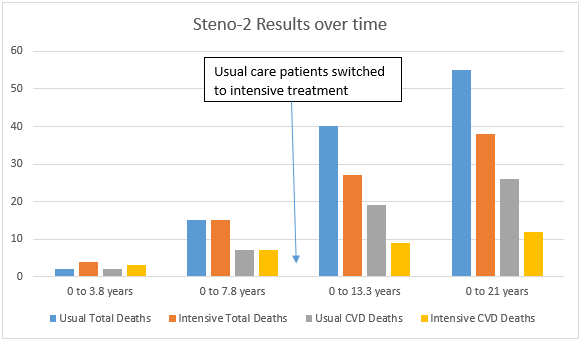

The first paper reported results 5.8 years after the study started. It found no difference in mortality, therefore there was no difference in life expectancy. There were 2 deaths in the usual group; 4 deaths in the intensive group. 2 CVD deaths in the usual group; 3 CVD deaths in the intensive group.

The next paper was the primary result paper, which reported results after 7.8 years of follow up. There was once again no difference in mortality between the groups, which means no difference in life expectancy. There were 15 total deaths in the usual group; 12 deaths in the intensive group. 7 CVD deaths in the usual group; 7 CVD deaths in the intensive group.

Now, pay attention to this, the experimental treatment differences were stopped and the usual care group was converted to intensive treatment. The next paper reported outcomes 13.3 years after the study started. There 40 total deaths in the usual group; 24 deaths in the intensive group. 19 CVD deaths in the usual group; 9 CVD deaths in the intensive group.

The last paper in the STENO study reported outcomes 21 years after the study started and found a big difference in mortality, when the total number of participants was less than half of what the study started with. The authors claim that this finding results in an 8-year increase in life expectancy.

Let’s take a slightly different look at the outcomes. Here is a graph of each of the deaths in the reports.

OK, so far we have a very small study with a funky hitch in the outcomes. Is this hitch at 7.8 years expected? Let’s look at some classic studies in cholesterol treatment literature for starters.

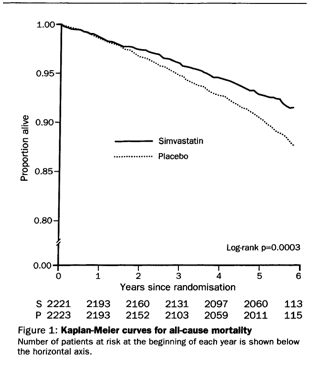

The very first study of treating cholesterol with a statin was the 4S trial. They enrolled a high-risk group of 4,444 patients who had survived an MI or who had proven coronary artery disease, and who had total cholesterol numbers between 210 and 310. Patients were given simvastatin or placebo. Here is the mortality outcome curve from that study. Notice the smooth even outcome over the duration of the study.

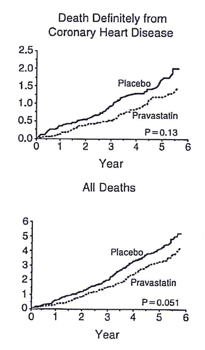

But what about patients without known coronary artery disease who had high cholesterol? The WOSCoPS study was the first one to treat patients without known coronary disease, so this more closely mirrors a typical primary care scenario. They enrolled 6,595 patients with a mean total cholesterol level of 272. Patients were given pravastatin or placebo. Here is the mortality and CVD outcome from that study.

As you can see from these 2 landmark studies, a patient needs to take the medicine for about 6 to 18 months before any mortality improvement is seen. After that, the performance of the medicine is smooth and consistent for years after it was initiated.

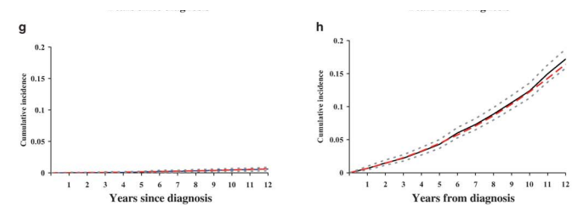

What about the contribution of treating diabetes more aggressively? Let’s look at one of the longest randomized controlled trials ever completed, the UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS). In UKPDS, they randomized 3,642 patients newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes into tight vs. loose control. The tight control group got oral medicines or insulin to keep their fasting sugars below 109. The loose group got meds if their fasting sugars were greater than 270. At the end of 10 years (though other arms of the trial went for greater than 20 years), the average hemoglobin A1c was 7.0% in the tight group and 7.9% in the looser group. The 2 graphs below show, on the left, the percent of patients who started dialysis; and on the right, total mortality. This study started in the late 1980s and some of the medications we have now weren’t available then, but you can see that the A1c levels are in line with excellent care here. You can also see that a tiny number of diabetics actually ever go on dialysis. You can also see that there is no mortality benefit for about 10 years, and then the effect after that is very small.

Another UKPDS study estimated that intense control would result in an increased life expectancy of 0.27 years over 16 years.

What about other studies of intensive glucose lowering? A meta-analysis of 11 trials including 34,533 patients found no difference in mortality. Three years later, the ACCORD study of 10,251 patients in the U.S. and Canada with diabetes and increased risk for CVD (prior evidence of CVD or multiple cardiovascular risk factors ) were randomized into 2 different concurrent blocks of aggressive or usual treatment. Its conclusion read “intensive BP or intensive glycemia treatment alone improved major CVD outcomes, without additional benefit from combining the two. In the ACCORD lipid trial, neither intensive lipid nor glycemia treatment produced an overall benefit, but intensive glycemia treatment increased mortality.” There was no improvement in overall mortality, therefore no increase in life expectancy.

Next, you might wonder OK, I see the smooth performance for one treatment for coronary artery disease and diabetes, but Steno-2 used 4 medications. Are there other studies besides Steno-2 that have looked at this issue? Of course there are! Let’s look at them. I won’t mention every study ever done in this arena, but here are some of the biggies.

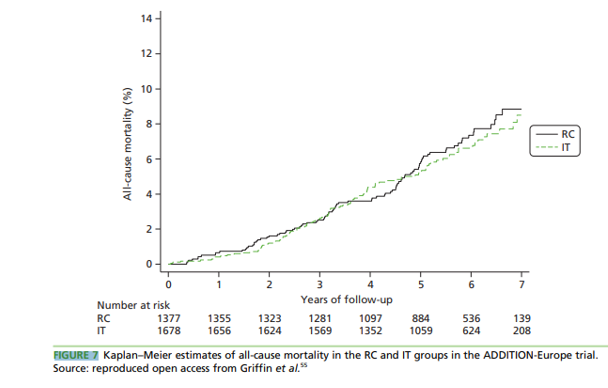

The ADDITION-Europe trial randomized 3,055 patients in 3 European countries who were newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. Patients were randomized into intensive management vs. usual care according to the 3 countries national guidelines. “Intensive” meant more medications and more available counseling to achieve lower targets for A1c (<7.0%), blood pressure (<135/85), and total cholesterol (<174). After 5 years, “clinically important improvements in cardiovascular risk factors” were achieved in the intensive group. There was no difference in mortality, CVD risk, or first CVD event.

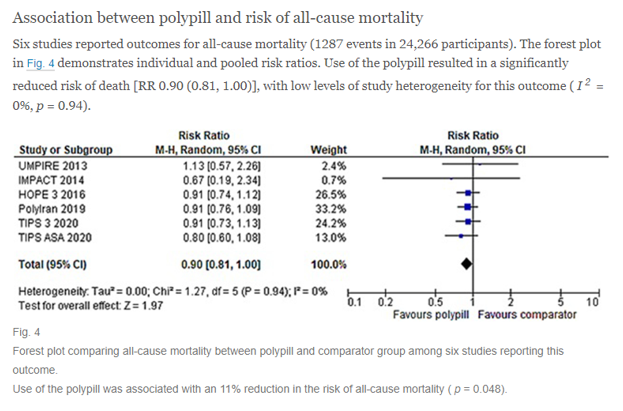

There is another set of studies that have a similar spirit of comprehensive CVD care called “polypill” studies. They typically contain 4 or 5 medications in once-daily pills such as statins, diuretics, beta blockers, ACE inhibitors, and aspirin. A meta-analysis of 6 polypill trials covering 24,266 patients that measured overall mortality calculated an 11% decrease that was barely statistically significant. Typical follow-up lengths for these kind of studies are about 5 years. Here is the forest plot from that study.

Cost-Effectiveness of CVD treatment

The Steno-2 authors actually published a cost-effectiveness analysis, so let’s take a look at what they calculated.

They used a standard approach of a Markov analysis to incorporate risk and event data. They based their model on the first 8 years of treatment. So there is the first funny thing. The Steno-2 study found no difference in CVD deaths or overall mortality at 7.8 years. Yet they state in the paper that there was a 1.9 year difference in undiscounted life expectancy. How can there be a difference in life expectancy if there was no difference in mortality? There can’t be, but let’s press on.

They say that the discounted difference in life expectancy was 1.0 years. They appropriately estimated that the treatment costs on the front end increase to pay for more drugs and clinic visits; and they also included in their model savings from future CVD events. The way they reported out the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) was a little strange, but the bottom line is that they estimated the primary ICER outcome as 2,538 Euros per quality-adjusted life year (QALYs, the standard outcome of the medical cost-effectiveness literature).

In case you missed the point, even the Steno-2 authors, using exaggerated projections of 8-year outcomes from a tiny study, still calculated that aggressive preventive treatment DOES NOT SAVE MONEY.

Summary

The Steno-2 study was a single outlier study with mortality results that are biologically implausible and contained less than 5% of the subjects than just one of the classic landmark trials in this literature; and less than 1% of the subjects in published meta-analyses.

All of the standard large trials in this literature find that patients have to take their medicines for 6-18 months before any real effect is seen. Then, the results are smooth and consistent over the life of the randomized trial. In the Steno-2 study, there was absolutely no difference in outcomes over 7.8 years, then a massive jump in deaths in the “control group” AFTER they were put on the intensive treatment. This means that the intensive treatment killed people!! (I’m being a little facetious here. There is a 99% chance the long-term Steno-2 outcome was nothing more than a statistical fluke. It happens all the time in small randomized controlled trials. If you want to learn more about this phenomenon, here is a paper by John Iaonnidis, MD, who is one of the gurus of evidence-based medicine.)

Take home points

Here is what you need to know about preventing cardiovascular disease in primary care.

· It helps a little. A better way of thinking about this is that treating high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and diabetes DELAYS heart attacks and deaths more than it PREVENTS heart attacks and deaths.

· The magnitude of the benefit for high-risk people is on the order of a few months of increased life-expectancy per chronic disease to maybe a year-ish.

o Actually, the Steno-2 cost-effectiveness study supports this statement. It treated diabetics with pre-existing kidney damage, which is a fairly high-risk group. It calculated an increase in discounted life expectancy of 1 year over 8 years of treatment. If it treated 3 different conditions and the outcomes were additive, then this works out to be about 3-4 months of life expectancy per disease.

· The magnitude of benefit for low-risk people is on the order of a few weeks of life expectancy per chronic disease. Low-risk could mean the patient is relatively young, 20s – 40s roughly. It could also mean the patient has a mild case of the chronic disease: barely elevated blood pressure easily treated with one common drug, for example.

· There are a few exceptions in really high-risk patients with bad versions of the common chronic diseases, but treating any of the common CVD prevention chronic diseases DOES NOT LOWER THE TOTAL COST OF CARE. In this arena, medical economics realities are like most other economic realities—BETTER OUCOMES COST MORE.

· Therefore, the Starfield-type findings that places with more family docs and fewer ologists enjoy better outcomes at a lower cost CANNOT BE EXPLAINED BY MORE CVD-RISK CHRONIC DISEASE CARE.

· And therefore, any efforts to “support” primary care in helping lower the total cost of care by beating on the family physicians to do more chronic disease care set them up to fail.

· Real efforts to use primary care to attempt to reduce healthcare costs must identify and support a completely different set of constructs such as

o Comfort with uncertainty in medical decision making (and an overall comfort with death)

o Providing actual comprehensive care of nearly 2,000 symptoms and diagnoses

o Incentivizing as few referrals to ologists as possible

o Real continuity of family physician to patient (not team to patient)

o Decreased emphasis on team-based care (I’ll talk more about this in the next post)

o Incentivizing family physicians to cover more patient responsibilities outside of 8-5 M-F.

o Incentivizing family physicians to have primary care responsibility for their own patients in the hospital

o Abandon the CPT billing system for family medicine.

o Creating micro-environments where the easiest thing for a patient to do when he/she has a concern is call or visit their family physician (as opposed to going to urgent care or the ER). This means that a live human actually is paid to answer the call, which means the practice is paid enough to pay for these humans. To achieve this, the family physicians must have slack in their work systems. Each of their days need enough of them present to handle surge capacity. Part of the justification for high charges in the ER is this concept. This payment concept needs to move to the primary care arena.

o Finding patients who are also comfortable with uncertainty and who are willing to make sacrifices for the good of the healthcare system.

OK, that’s a lot to digest. I’ll post part 2 of this discussion in about a week.

Recent Comments